The Story of Britain’s Most-Popular Printing Toy

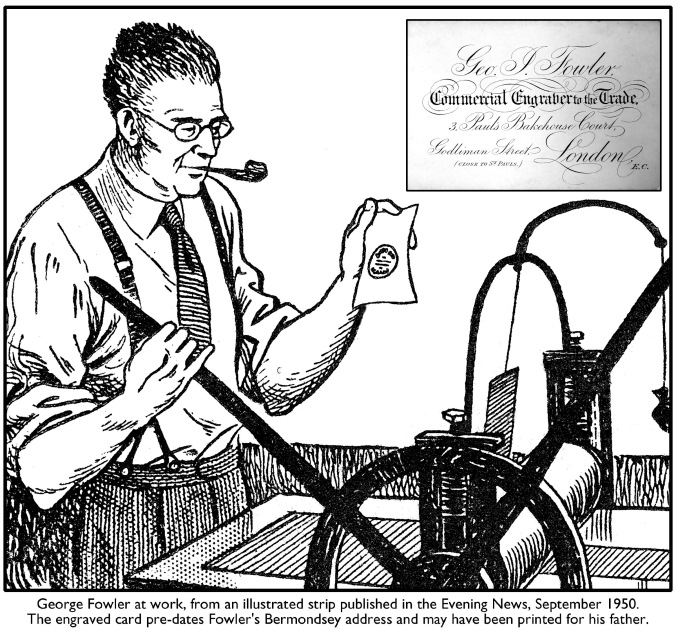

Nineteen-twenty-two was a good year for budding printers. In the leafy London suburb of Twickenham a young man called Donald Aspinall set up the Adana printing machine company, while a short distance to the east, in the City of London, three businessmen were laying the foundations of an equally famous printing-related company. The name of their small enterprise—The Charter Stamp Company—means very little today, but their most famous product—the John Bull Printing Outfit—is probably more fondly remembered than the Adana press.

John Bull Printing Sets are among Britain’s oldest and most popular toys and the most common childhood introduction to ‘relief printing’. The toy was looked upon as the perfect ‘stocking filler’ by generations of doting parents and grandparents. Cheap and simple to use, they provided hours of fun for little fingers and a much more typographically creative form of wallpaper gratffiti than crayons alone could ever do.

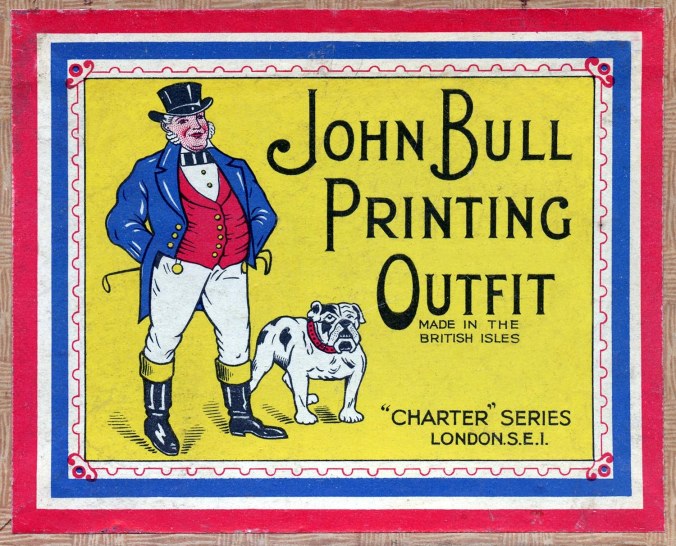

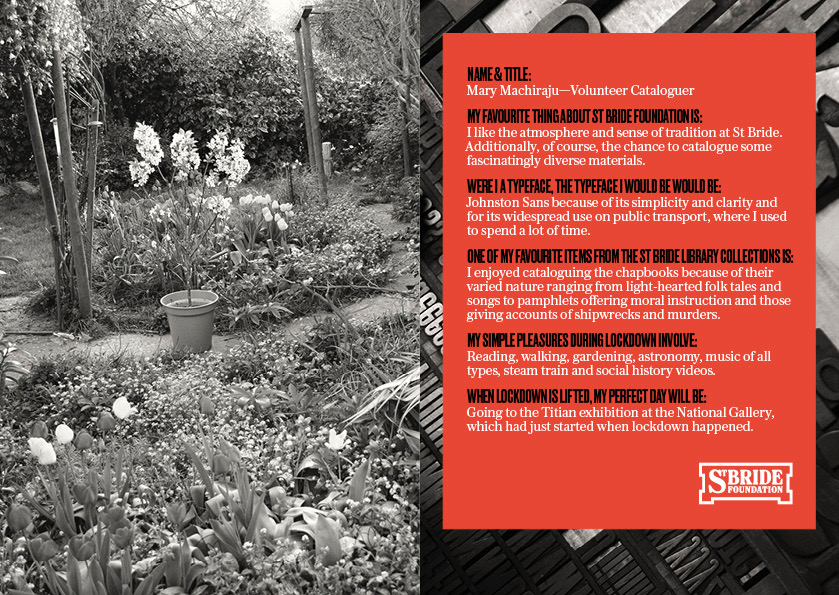

St Bride Library has a small number of John Bull outfits. Acquired over the past century or so they are not catalogued, but form part of our Special Collections. The manufacturer’s name varies according to the age of each set and boxes sometimes carry “Charter Series”, “Carson-Baker” or “Carbak” names and logos, depending upon when they were made.

Charter Series: The Zoo Printing Set

The Carbak Picture Printing Outfit

In 1922 rubber stamp maker John William Baker of Sydenham, Harold Christie, a toy dealer from Staines, and bulb-grower Thomas Baker of Spalding, established the Charter Stamp Company with capital of £3,000 divided into £1 shares. This was a very healthy sum indeed for 1922, equivalent to around £175,000 today.

There is documentary evidence that Charter Stamp had traded for a number of years before the creation of the 1922 company. A number of late Victorian and Edwardian rubber stamping sets for children also carry the “Charter” trade mark. A 1916 sales receipt from a Wandsworth stationer also clearly refers to a John Bull Printing Set, eleven years before the trade mark was registered with the Department of Trade.

The incorporation paperwork for the company is dated 23rd March 1922 and states that the company was founded “to carry on business as manufacturers and dealers in stamps and dies, toys, stationers’ sundries…and articles of any description”. The directors set up their head office at 57 Old Street in the City of London and spent the next five years selling stationery and making rubber stamps for office use. The manufacture of rubber stamping toys for children was carried on alongside these commercial activities.

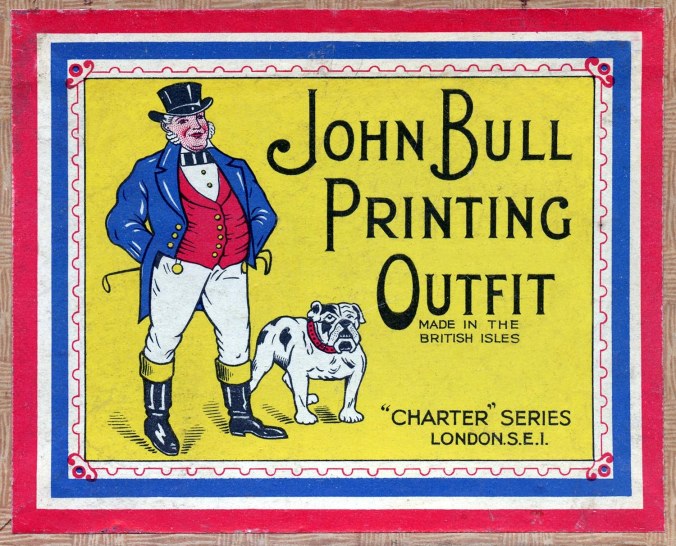

Five years after the foundation of the Charter Stamp Company, in February 1927 the John Bull trademark was formally registered with the submission of artwork which would be used in packaging design for the next five decades. The original watercolour of John Bull and his dog survives in the National Archives at Kew. The distinctive box design became so recognisable that in January 2009 The Guardian political cartoonist Martin Rowson showed the Chancellor of the Exchequer trying to re-start the UK economy after the global financial crash with a John Bull Quantatative Easing Kit. The iconic box design was parodied in the newspaper cartoon, which can be viewed here.

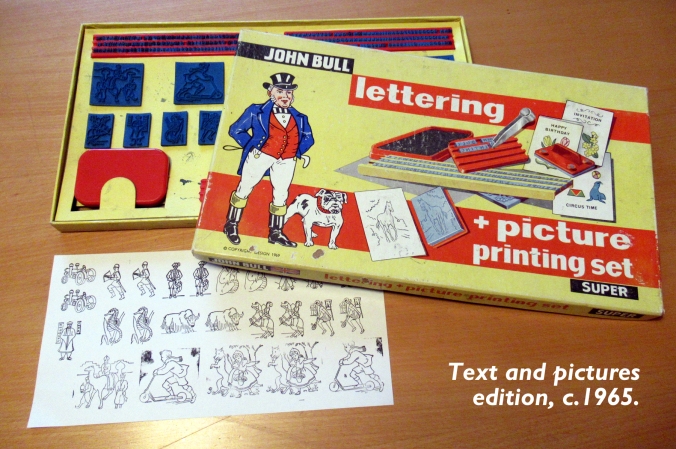

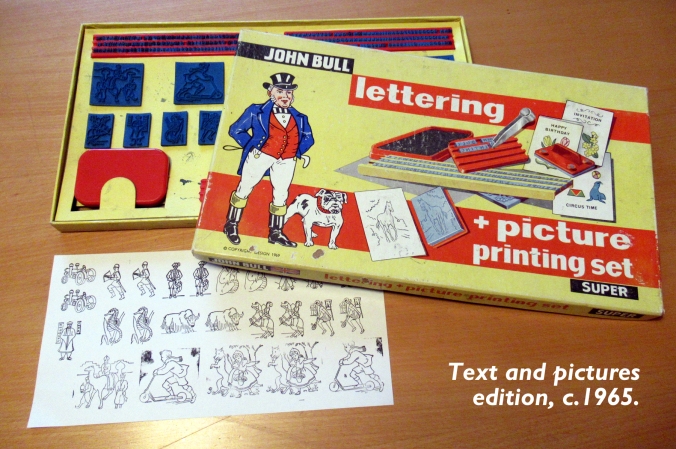

Early John Bull sets consisted of just upper-case characters, around 12 point in size. Rubber illustration blocks would be introduced into the sets by the late 1920s, but had also been sold separately under the “Charter” name for three decades or more. Early sets sometimes included a rubber stamp showing the John Bull figure illustrated on the box lid. By the early 1930s a slab-serif typeface with upper and lower-case characters had been introduced and more expensive sets included printing blocks showing a clown, juggler, and Native American Chief and farm or zoo animals.

Endless versions of the rubber stamping sets were issued from the company works in South Norwood. Sets were numbered anywhere from “1” to “250”. There were also “Special” sets which were sometimes indistinguishable from the basic kits. The smallest set was marginally larger than a box of kitchen matches while the largest dwarfed a standard Monopoly board game box. The most commonly seen survivors are sets No. 4, 8, 18 and 12.

Perhaps the strangest John Bull product is that which uses Monotype. These sets, with Monotype metal types, appeared soon after the WW2 and British patents dated October 1946 cover the special typeholder required (Patent 617,495) and the custom-designed cardboard typecase (619,092). The set contained 120 pieces of 12pt Monotype Gill Sans, although, rather curiously, the accompanying instruction leaflet was set almost entirely in Stephenson Blake’s rival sanserif, Granby. A special wooden typeholder accommodated two lines of type, held in place with a thin wooden wedge. Only en-spaces were provided for use between words. A foam-rubber ink pad with non-toxic, water-based ink was supplied, so the results cannot have been very satisfactory. By 1950 this metal variant had been discontinued.

John Bull Metal Type Printing Outfit using Monotype Gill Sans

The Charter Stamp Company moved head office several times in the early years of trading, but would eventually settle at 57 Southwark Street, London SE1, where the sets were also produced. The company proclaimed the John Bull Printing Set to be 100% British made. This was true. Boxes were made on site, the rubber letters were moulded and vulcanised at the factory and even the non-toxic water-based ink was brewed up in large buckets. The product range expanded and by the early 1960s included a small rotary hand press (Model No. 5) which could accommodate several line of rubber type in a grooved drum, rather like the American Multigraph printing machine.

On 25th May 1946 a meeting was convened to discuss a possible change of name for the company. The maiden name of founder John Baker’s mother was Carr, and he was therefore “Carr’s son”. Baker was of the opinion that double-surname companies carried more commercial clout. There was a famous precedent for this, with tea importer and blender Arthur Brooke inventing a non-existent business partner—Mr. Bond—in 1869. On 11th July 1946, the Charter Stamp Company became Carson-Baker Limited and the “Charter” trademark became “Carbak”. “Charter Series” packaging materials were still being used in the 1950s until the stockpile of old box designs was gradually exhausted, so the two trademarks often appeared side-by-side

In the late 1970s costly plastic injection-moulding equipment was purchased for soft polymers, although the old vulcanised rubber system was retained for foreign language sets. The export market was important as a source of income, but the cost of producing new moulds for foreign territories was prohibitive. In the 1970s between 60,000 and 100,000 John Bull Printing Outfits were being made each year.

Surplus manufacturing capacity allowed the production of components for another maker of educational rubber stamps. The Mapograph Company of Chiswick produced a roller printing system which allowed images to be applied to the pages of school exercise books. Maps, biology diagrams, trees of Britain and technical illustrations made up a substantial library of stock images for scholastic use. Invented in 1924 by Alfred Kings and Bernard Simons, the Mapograph system used a deep relief rubber stamp on a wooden roller. A spring-loaded mechanism re-set the roller, giving a perfect print (theoretically) on each page. Mapograph inks and stamp pads were made by Carson-Baker. When the elderly owner of Mapograph retired in 1978, the company became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Carson-Baker.

Toy manufacturer Cowan DeGroot were the largest distributor of John Bull sets and when John Baker retired in the 1960s, Carson-Baker was acquired by their main customer. The “Codeg” trademark replaced “Carbak” on packaging and advertising material. Following the takeover, Cowan DeGroot expanded the range of products. By 1970 children could buy a John Bull farmyard set, backgammon, draughts and even a board game version of the BBC Mastermind quiz show. Frustratingly for Codeg, this had to be called Masterbrain because a rival board game made by Invicta plastics and unconnected with the BBC series, already used the name Mastermind. Nevertheless, the packaging for Masterbrain proudly stated that it was “brought to you by the makers of the famous printing outfits”.

Cowan DeGroot sold the John Bull trademark to Dekkertoys of Peterborough in the late 1980s, but the famous printing sets are no longer available. Second-hand sets occasionally appear on Ebay but new printing outfits are no longer manufactured.

My passion for letterpress and typography was sparked by the gift of a John Bull set at the age of five. Sadly, with the demise of John Bull printing sets, young letterpress printers today must seek their inspiration elsewhere.

Bob Richardson

Library Manager

St Bride Foundation

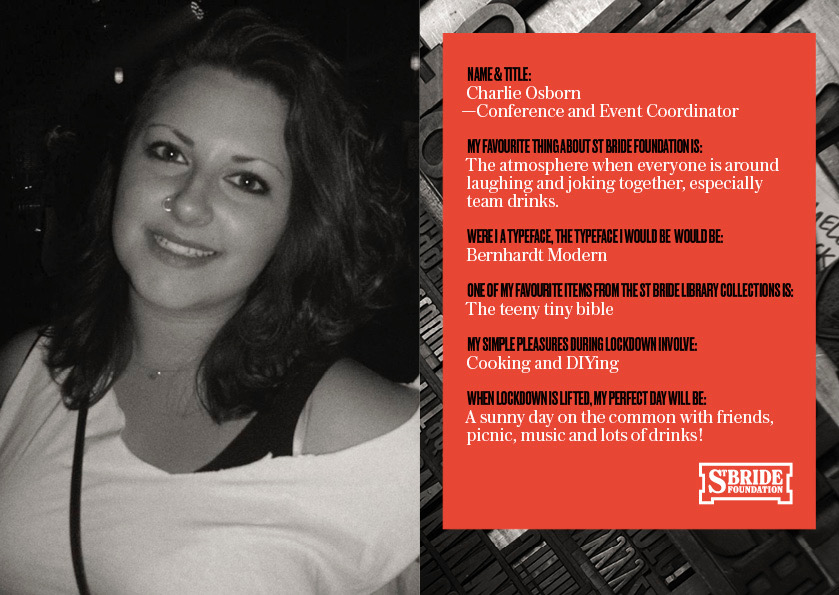

Charlie Osbourne – Conferences and Events Coordinator

Charlie Osbourne – Conferences and Events Coordinator

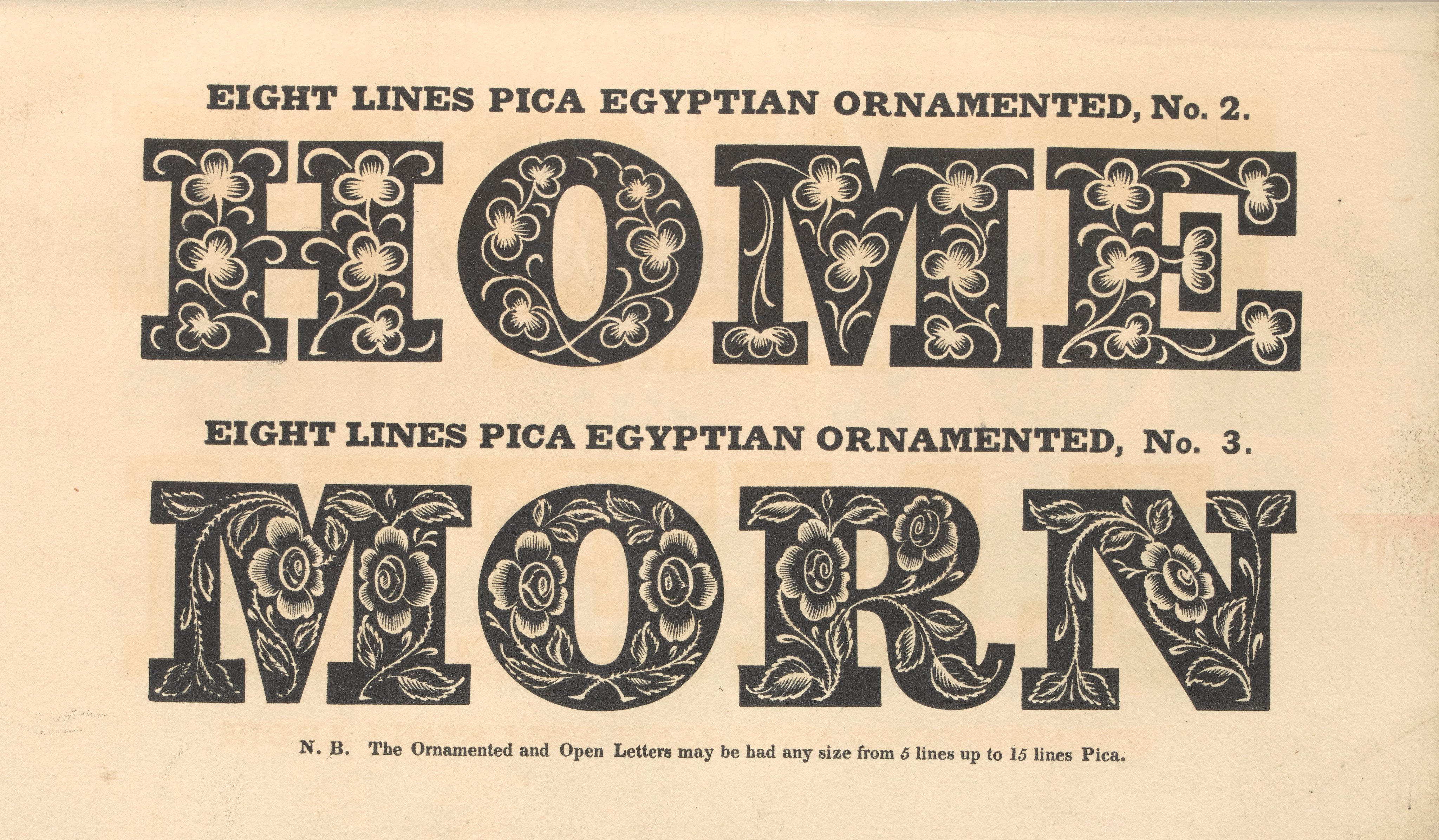

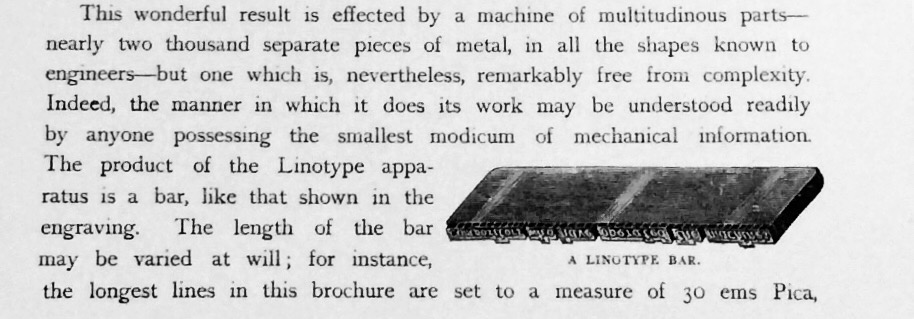

Chaostype was a method of producing and printing complex ‘organic’ images from the raw material of letterpress itself – molten type metal. John Franklin Earhart was the inventor of this process used for a short period in the late 19th century which relied upon the unpredictable and random qualities of chaos.

Chaostype was a method of producing and printing complex ‘organic’ images from the raw material of letterpress itself – molten type metal. John Franklin Earhart was the inventor of this process used for a short period in the late 19th century which relied upon the unpredictable and random qualities of chaos.